Barcelona’s Car-Taming ‘Superblocks’ Meet Resistance

The plan to ban through traffic from much of the city could still be a game-changing model.

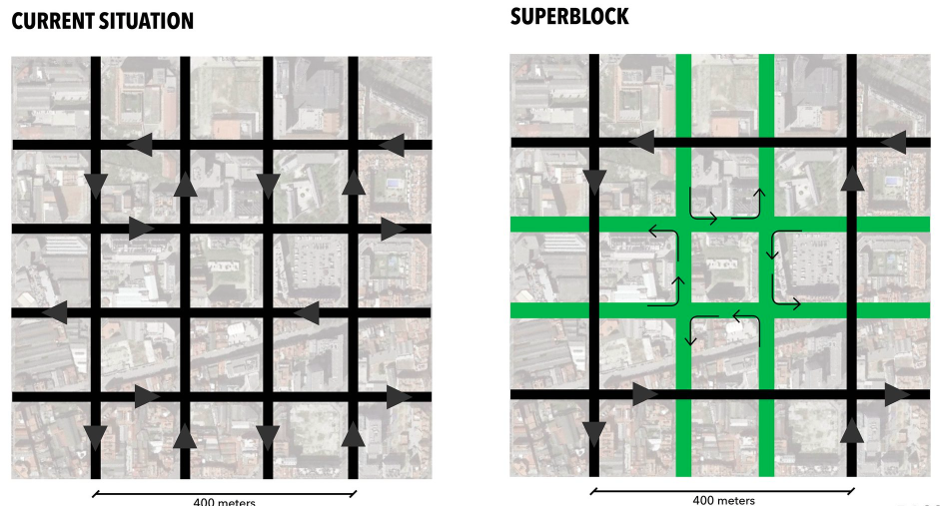

Barcelona’s plans to slash car traffic may be some of the most innovative in the world, but right now their introduction isn’t going all that smoothly. Since last year, the city has been introducing so-called superblocks. These are square sections of the city’s grid made up of nine actual blocks, with a combined area of just under 40 acres, where through traffic is permitted only on perimeter roads. The idea of these superblocks is to cut pollution and car collisions while making more space for pedestrians and cyclists. As yet, it seems that not everyone is convinced.

Last Sunday, some residents in Barcelona’s Poblenou neighborhood took to the streets to protest against their own local superblock, introduced in September, which they say is making their daily lives far more complicated by forcing local drivers to take long, circuitous routes around the neighborhood. A small local protest like this might not amount to a whole hill of beans, but Barcelona’s current superblocks (of which there are four) are just the beginning of a plan to extend the traffic model across the entire city by the end of 2018, by which time 500 superblocks should cover the city. Already, five more superblocks are slated for introduction this year alone, and more public resistance could well be on the way.

The concept could certainly reshape the way the city functions. Superblocks, known as Superilles in Catalan, work by limiting the number of roads that cars can use to cross the city. Following the diagram below, through traffic is permitted only on roads around the perimeter of each superblock, where new bus lines are installed to mop up residents who have abandoned regular driving. The streets within the block have a low 10 kilometers-per-hour speed limit and allow access only for local residents, public transit, delivery vehicles, and emergency services. They are modeled so that vehicles can use them only to drive into the superblock then backtrack out again.

Once this system is in place, the less car-encumbered streets are redesigned, extending pedestrian space and and allowing for amenities such as playgrounds. Currently, Barcelona has three fully complete, redesigned superblocks, and one (the superblock in Poblenou) where traffic has been re-routed using barriers and bollards, but new pedestrian amenities and landscaping have not yet been installed.

The Poblenou protestors say that their superblock has made driving a Kafkaesque nightmare. One local said that thanks to rerouting, a car journey of 900 meters (just over half a mile) had tripled in length, while traffic around the perimeter had also increased. Continuing this pattern across they city, they fear, would make navigating Barcelona by car as complex as solving a Rubik’s Cube.

Are such criticisms fair? To a limited extent, yes. It seems highly likely that, after a superblock covers an area, driving within it would become a slower and more longwinded experience. But like almost any plan to discourage driving and encourage walking and cycling, that’s exactly what is supposed to happen. If it didn’t change habits like those of the resident driving half a mile when he could use a bus or bike, the plan would have failed. In Barcelona’s three mature superblocks—located in the Gràcia and Born neighborhoods and now fully equipped with pedestrian improvements, wider sidewalks, and more street furniture—the advantages have gradually sunk in and resistance has largely evaporated.

Meanwhile, the architect of the superblock concept, Director of the Barcelona Urban Ecology Agency Salvador Rueda, shared some impressive results with Catalan broadcaster CCMA this week. Focusing on the superblock installed in Gràcia, Rueda found that since 2007, walking had increased in the area by 10 percent and cycling by 30 percent. Driving in the superblock as a whole had fallen by 26 percent, while in the internal streets, it had fallen by 40 percent. If this pattern is extended across the city by 2018, Barcelona could finally manage to improve its currently poor air quality, where pollution habitually rises above E.U.-prescribed safe levels.

It’s an approach that could catch on elsewhere. With its flat, regular grid, Manhattan is often cited as a potentially good host for superblock planning. Paris, meanwhile, is poised to ban non-local traffic from the Marais neighborhood, turning the city’s 3rd and 4th arrondissements into a kind of de facto superblock.

Inevitably, making inner-city driving less convenient comes as a shock to some drivers. But the end result—a cleaner, safer city where every street corner is an open-air living room—is so seductive that densely built cities will find it hard to resist making superblock plans of their own.

Comments

Post a Comment