To Fix the New York City Subway, Fix the Schedule

A forensic transit scientist says the MTA needs timetables its human operators can manage.

On a recent Monday afternoon at Grand Central Station, strings of subway cars clatter up to the 4/5/6 platform. As trains arrive every four minutes or so, doors open and shut quickly, rarely parting longer than the 10 seconds they’re supposed to. They stick to schedule.

But as afternoon melts into evening, larger numbers of passengers surge onto the platform. “Dwell times” brim over their scheduled mark, as doors linger open and conductors bark at riders to press toward the center of the car. As trains hang longer than they’re supposed to at successive stations, running times stretch further and further past what’s planned.

The steady accretion of micro-delays during peak hours can unleash all manner of subway chaos. But it’s not necessarily the fault of the drivers.

“On every line I have studied, they’ve under-scheduled the peak,” says Adam Rahbee.

In other words, it’s not just that operators are driving behind schedule. Schedules are going too fast for the operators.

Wearing salmon shorts and a thick wrist watch when I meet him at Grand Central, Rahbee sports a slightly nervous grin that belies his expert confidence. He’s an MIT-trained metro rail researcher who has worked inside some of the busiest systems in Europe and North America. A self-proclaimed “forensic” transit analyst, he has scrutinized archival data for 23 subway lines in Boston, Chicago, and London, looking to understand how and why delays crop up. Rahbee has also served as a peer expert for the U.S. DOT, published dozens of papers, operated CTA trains, and interviewed drivers, dispatchers, and service planners around the world.

And he believes he has a solution to New York City’s subway meltdown: Rewrite the timetables.

Here’s the idea: Drivers and dispatchers have their idiosyncratic habits to adapt to rising ridership and signal breakdowns. Crunched and harried as they make round trips, they’re also losing minutes to meet their basic needs. The tiny delays this creates can cascade into bigger ones later in the day, feeding a more general system-wide collapse.

It’s the human side of the subway’s problems that no one is talking about. And it might be a lot cheaper to fix than new subway cars.

***

One hundred and thirty years ago, North American railroad engineers standardized time zones to impose temporal order over a vast continent, and avoid crashing trains into each other. Not long after, the New York City subway set the world standard for glorious, 24-hour service.

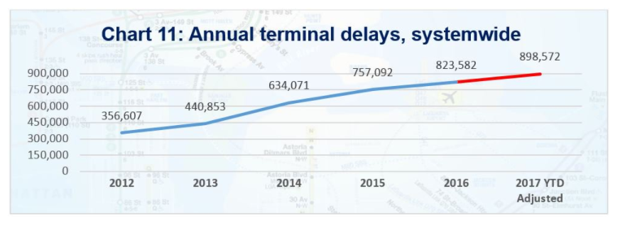

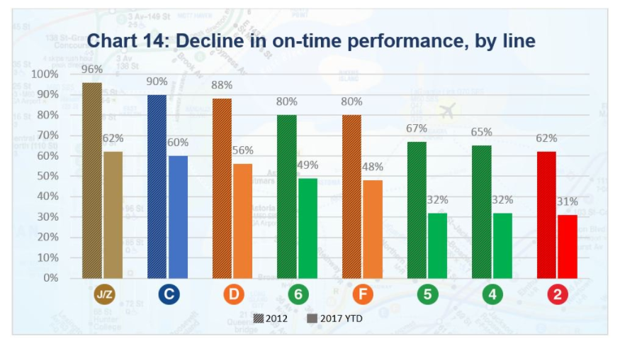

These days, human-driven rail in NYC is feeling its age. In the first four months of 2017, just 63 percent of the city’s subway cars arrived at the end of their lines within five minutes of their scheduled times—bringing “on-time performance” down 21 percentage points since 2012.

The effects on passengers are well documented: Lost time means lost appointments, jobs, and wages, perhaps billions of dollars annually.Crumbling infrastructure, nonstop construction, signal slow-downs, labor costs, and riders themselves are the oft-heard explanations for why the trains can’t run on time.

But there’s another, largely overlooked element that is worth paying attention to, some operators and analysts say. Even in the absence of signal failures, door-holding, and sick passengers creating delays, drivers are struggling more than ever to stick to the scheduled running times on the busiest lines. Not only do timetables measure delays (i.e., whether trains are arriving “on time”), they may also be causing them—because people are not machines.

As conductors hold trains a little “too long” to accommodate rush hour crowds, operators run out of scheduled time at the end of the line. To maximize efficiency, timetables generally allow no more than a handful of minutes of “recovery time” for trains to turn around and head back into service. That’s usually when operators are supposed to receive breaks.

But if a train arrives at its terminus significantly later than scheduled, the operator still has to depart for her return trip on time. That means she might have to forgo her break—which can wind up dragging down trains further down the line.

“Let’s say I’m halfway through my return trip, and I absolutely have to go the bathroom,” says Noah Rodriguez, an MTA train operator on release from his regular route on the 6 train, one of the worst-performing lines in the system. (Rodriguez currently works for TWU Local 100, which represents operators.) “I’ve got to get off the train, secure it,” he says. “Now, that train has to wait for me.”

Drivers who hold trains for badly needed breaks—or stop their train and unload passengers because they have to clock out for the day, which can also happen—catch dispatchers off guard, and can easily create a cascade of delays. Think of New York City’s subway system like branching pipes: A clog on one line often means restricted flow on at least one other, further upstream.

Hold-ups resulting from tight timetables are common on some lines. In his experience on the 6 train, “that kind of thing happened daily,” says Rodriguez.

“We can never stick to the schedule,” says Marcia Lane, a 7 train operator.

So, if drivers are rarely on time, why do schedules exist at all? Would there even be delays to measure if they didn’t?

This might sound like a stoner reverie. Passengers don’t care about schedules; they just want to know that there’s a train coming soon. Timetables, however, do matter to planners, dispatchers, and operators. They determine the number of trains that can be in service at a given time, help manage signal timings and employee hours, and prevent collisions. “The subway is like a chessboard,” says Rahbee. “There is only so much room, and you can only move the pieces a certain way.”

MTA service planners review schedules every six months. Sometimes they make revisions, using inputs such as ridership counts, train speeds, and car lengths. They do so with the knowledge that the times are a little more optimistic than reality permits. Union contracts don’t really incentivize speedy performance; in some ways, planners design timetables to keep drivers on their toes.

It’s hard to finger any single factor in the subway’s dismal performance with a degree of magnitude. But systemwide construction-related disruption, failing signals, aging cars, and rising ridership counts may be amplifying the deleterious effects of overly ambitious schedules.

The union has taken note. Kia Phua, the vice president of rapid transit operations at TWU Local 100, says unbreathable schedules have become a performance issue in the past two years. Operators pressed to keep driving without rest might run at slower speeds, accidentally hit emergency brakes, or fail to read signals correctly. Some have filed grievances with the MTA.

“We’re human beings,” says Phua. “We’re not robots.”

Phua says the MTA is working with TWU to solve the break time issue, which may include reducing trains on certain lines. That gets closer to what Rahbee sees as the problem, which is bigger than any particular labor policy. To him, lost break times are a symptom of a schedule that doesn’t allow enough room for humanity.

As an analyst in the planning department of the London Underground in 2006, Rahbee found the same issues on some of the most notoriously congested lines. For the Northern Line—known to Londoners as the “misery line”—Rahbee created hyper-detailed time-distance charts that showed a predictable pattern: delays cascaded from unrealistic running times. He spent months interviewing operators and dispatchers about how they worked to adapt.

Rahbee’s findings mirrored what MTA operators describe: London workers came up with their own processes to cope with insufficient running times, which didn’t necessarily get reported back to service planners. The solution, Rahbee and a few other colleagues believed, was to write a timetable that actually reflected operators’ working environment—and to build communication between those writing the schedules and those trying to adhere to them.

London planners were reticent to let go of the old input-output models that they, like many agencies, had used for decades to create schedules. As Rahbee recounts in a 300-page, self-published tomeoutlining his findings, tensions ran high as a result of the proposed changes. Rahbee resigned from his position in 2008, largely for health reasons. But the agency took his advice to redesign the timetables, and saw smoother service as a result. The Tube has continued to see reliability improve.

Rahbee sees his exhaustive, bottom-up approach—which he developed over previous jobs in Boston and Chicago—as an honest way to understand the embedded frailties of a human-run subway system. He plans to pitch such an analysis to New York Governor Andrew Cuomo’s “Genius Transit Challenge,” which will award $1 million to out-of-the-box ideas to fix NYC’s ailing system. If MTA planners reimagined the scheduling process through rigorous data analysis and investigation of its practical operations, he guesses it could bring on-time performance on certain lines within the 90 percent range.

Clearly, the subway’s problems are not limited to its schedules. But even if such revisions improved service moderately, the return on investment could be huge. Today’s “big data” processing software makes digging into the where, when, and why of transit delays much easier than in Rahbee’s early days. Compared to the multi-billion dollar capital investments the system requires, tweaking the timetables would be virtually free.

Unfortunately, politics may be preventing it. Adding more running time where it’s needed might lead to smoother, more reliable service. But it could also mean fewer, more evenly spaced trains on the tracks, which would look a lot like “less” service on paper.

“It’s almost an admission of defeat,” says Zak Accuardi, an analyst at TransitCenter, the transit research and advocacy group. But Accuardi agrees that problems with schedules need to be accounted for. “Without acknowledging those kinds of challenges, it's hard to encourage elected officials to make big changes the system needs.”

MTA representatives did not return requests for comment for this story, citing a lack of time due to an agency-wide audit underway.

***

This admission of defeat is, in effect, an admission of humanity. In July, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority announced an $800 million plan to rescue the system, with steps that include adding extra cars to some lines, stripping seats to make more room, and hastening signal and track repairs across the system. But fixing the system also requires reckoning with its biological elements. Signals, cars, and tracks don’t make the subway run. People do.

At least for now. Metro rail systems are due for a mechanized takeover, arguably even more so than private cars. London and Parisare gradually automating their systems, as dozens of cities (and airports) already have. But apart from the AirTrain at JFK, New York City has only one, semi-automated line—the L train. It’s also the most reliable subway line in the city.

Comments

Post a Comment