To Build a Better Bus System, Ask a Driver

The people who know buses best have ideas about how to reform the system, according to a survey of 373 Brooklyn bus operators.

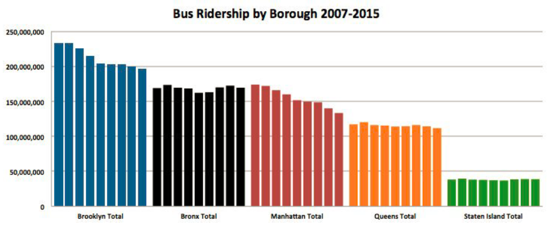

The facts are stark: Bus ridership in New York City is in a state of free fall. Ridership losses in the boroughs of Brooklyn and Manhattan are even more alarming.

This isn’t a secret. Advocacy groups have agitated for reforms for years. The Metropolitan Transportation Authority recently released a bus action plan intended to increase service quality, and with it, ridership. So far, the plan has few details, but it primarily focuses on technological and technical improvements, including all-door boarding, transit signal priority, and the distance between stops. While these improvements are needed, we believe any plan could benefit from input from a very critical element in the system: the drivers who sit behind the wheel.

Under the auspices of the Marron Institute of Urban Management at New York University, we are in the process of developing a bus redesign plan for Brooklyn’s bus network, in the hopes of influencing the transit reform process. Our plan will argue that combining technical and technological improvements with input from local bus operators and passengers who experience the network every day will make for a better system. Unlike trains, buses bring operators and passengers into direct contact with each another. Drivers answer passengers’ questions, help those with walkers and wheelchairs, and endure traffic on a daily basis; they have a unique perspective and intimate understanding of how the conditions on the road impact the bus rider experience.

Brooklyn is perhaps in greatest need of their contributions. It is the most populous borough, with the greatest number of bus riders, and it lacks the subway coverage of Manhattan. Its streets are not an orderly grid; running efficient transit is a challenge, and lessons learned here could be applied to other cities. And, as this chart shows, ridership in Brooklyn has been dropping dramatically over the last decade.

In our research, we sat down and spoke with 373 bus operators in Brooklyn. They described their experiences and helped us understand how to combine their observations and specialized knowledge with technical tweaks and improvements to tailor better solutions.

The top fix they’d like to see is off-board fare collection. Managing the farebox creates lots of opportunities for conflict with passengers. According to the Transport Workers Union Local 100, 75 Brooklyn bus operators were assaulted in 2017, in part because of disputes over payment. Relatedly, some 90 percent of the bus operators who responded to our survey said that all-door boarding, which would be made possible by off-board fare payment, would make them more effective at their jobs, the highest show of support for any change.

The second most important issue they highlighted was traffic and bus lane enforcement. The two issues that cause operators the most stress are double-parked vehicles (79 percent) and traffic (63 percent). In addition, 82 percent of operators said reduced congestion would make them more effective at their job. This finding is especially salient because New York has already rolled out camera-enforced bus lanes on some routes. Operators told us that these lanes don’t do enough to keep buses from getting trapped behind double-parked vehicles, taxis that are picking up or dropping off, and vehicles turning in front of them.

Many operators also expressed a frustration that road users such as bikers and pedestrians might be familiar with: They get no respect. “Bikes have dedicated lanes, so why not us?” said one. This wasn’t a complaint about cyclists, but a recognition of where buses seem to land in the hierarchy of road users. Over the last decade, New York’s streets and roadways have been redesigned to accommodate pedestrians, bicyclists, and even parking. Policy has been amended to make room for e-hail and green taxis. Even the oft-overlooked “dollar vans” that shuttle around outer-borough commuters have scored a few legislative victories in the last five years. Many of these changes have improved the city’s public realm, but what has been done for the bus? Relatively little. Select Bus Service—New York’s version of bus rapid transit—has rolled out slowly. As the bus operators reminded us, camera-enforcement isn’t doing enough to keep other types of traffic out of SBS lanes.

In addition to these issues, operators complained that unrealistic schedules prevent them from tending to basic needs such as going to the bathroom or grabbing a bite to eat in between trips. The human factor in bus scheduling is an ongoing challenge, and it’s currently addressed via the “personal”—a 20-minute rest break taken at the operator’s discretion, on an unlimited basis, to allow for some flexibility in an otherwise rigid schedule. By definition, the “personal” is not administered predictably or scheduled in advance. Some operators take multiple personals a day; others limit them to once or twice a month. While these breaks create time in the schedule for the operator, it defeats the purpose of having precisely timed schedules. Resolving schedule conflicts requires either increasing time between trips so that operators have a break between arriving and departing from a terminal, which costs money, or improving scheduling and dispatch. Dedicated bus lanes, signal priorities, and other driver-supported treatments that free the bus from car traffic could also help create greater certainty in schedules.

Comments

Post a Comment