Police Killings and Violence Are Driving Black People Crazy

Two new studies point to how police killings and violence harm the mental health of African Americans and students—even those who have not been exposed to the incidents.

Allegheny County District Attorney Stephen A. Zappala Jr. has filed homicide charges against the East Pittsburgh police officer, Michael Rosefeld, who shot and killed the unarmed teenager Antwon Rose Jr. This was one of the top demands of people who’ve been protesting the killing. Zappala also cleared Rose of any wrongdoing.

This announcement comes two days after Rose’s loved ones gathered at Woodland Hills Intermediate School for his funeral. While the service was reserved for family, friends, and schoolmates, it’s clear that his death has made an impression on many people outside of this community. The protests held over the last week were led by people who live across the Pittsburgh region, and his death was commemorated on social media by celebrity figures who are thousands of miles removed the area.

Two recent studies help explain how police killings and violence end up having such a broad impact, in many cases harming the mental health of African-Americans and school students—even those who have no direct involvement in incidents like these.

The first study, “Police Killings and their Spillover Effects on the Mental Health of Black Americans,” published June 21 in the medical journal The Lancet, finds that black people report having poor mental health days in the months after an unarmed African American has been killed by police. The “spillover effect” denotes the finding that such police killings tend to mentally affect African Americans in general, regardless of whether they have a personal connection to the person killed or not.

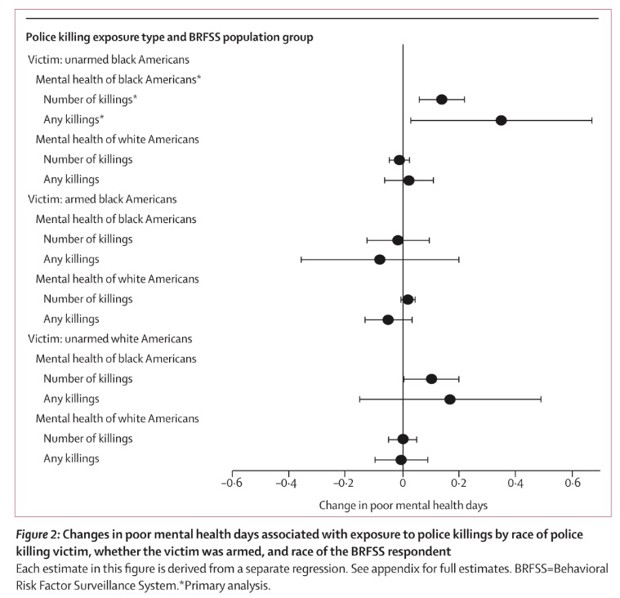

The study was led by a team of researchers from the public health schools of Harvard and Boston University. They linked data from the Mapping Police Violence database with data from the 2013–15 US Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), run by the Centers for Disease Control, to identify when BRFSS survey participants reported suffering from poor mental health and the number of police killings within the state they live in. African Americans reported having these problems more often within the first two months of a police killing. The number of poor mental health days increased with the more cases of police killings in their state. The study only found that police killings of unarmed black victims had this effect, and that it only affected African Americans.

“We found absolutely no effect on white people when an unarmed black person is killed,” says Jacob Bor, a researcher at the Boston University School of Public Health. “We were not surprised by that finding. It speaks more to the specific nature of this exposure, in the way that it connects to both present and historical aspects of racism.”

For the Antwon Rose case, this means that on top of the anguish suffered by his loved ones, African Americans across the city and state can expect to have bouts of depression, anxiety, and other attacks on the psyche in the weeks ahead.

Rose’s high school peers and classmates will likely experience their own acute mental breakdowns in coping with this, especially those who live in neighborhoods where violent crime is prevalent. Research already shows that students who live in violent environments suffer from depression, attention disorders, sleep deprivation, and other psychological maladies that can cause them to perform sub-optimally on schoolwork.

The other study that may help explain the impact of Rose’s death notes that violent crime trauma doesn’t just impact the mental health of students who’ve been directly involved with it, but rather, it spills over to other students throughout the same school. In her study, “Neighborhood Violence, Peer-Effects, and Academic Achievement in Chicago,” published earlier this month in the journal Sociology of Education, John Hopkins University researcherJulia Burdick-Will analyzed data from Chicago Public Schools, the Chicago Police Department, and the University of Chicago Consortium on Chicago School Research, to measure the impacts on schools that serve students from highly violent neighborhoods.

Prior research assumed that only students who’ve been exposed or victimized by violence themselves would have deficient school performance, or that only schools located in the most violent neighborhoods would register substandard grades and test scores. However, mental health problems from exposure to violence are not contained to just those individual students or areas. Burdick-Will found a “peer-exposure” effect that threatens the mental well-being of the classmates of students who’ve been exposed to violence, no matter whether those classmates have themselves experienced violence, or where the schools are located. Reads the study:

The estimated negative relationship between peer exposure to neighborhood violence and individual achievement is substantial. These estimates are larger than those of peer neighborhood socio-economic disadvantage and larger for students from safer neighborhoods. Survey data suggests that these results are related to increased reports of disciplinary problems and reductions in perceived safety and teacher trust in cohorts with larger proportions of students from violent neighborhoods.

Classrooms that have large numbers of students who’ve been exposed to violence end up having lower test scores than students with fewer or no students exposed to violence. The negative impacts are found in both math and reading, though worse for math. Students from these classrooms also are “substantially more likely” to be disciplined for behavioral problems and have lower levels of trust in their teachers. While Burdick-Will only looked at Chicago, she writes in the study that the same peer-exposure effects are “possible” in other cities that have neighborhoods with high levels of violence.

“The problem is that we have really serious violence issues in certain parts of the city and a lot of urban residents tend to feel like, ‘Well, it's not immediately around me, so it doesn't affect me,’” says Burdick-Will. “But I think my research and growing research on urban violence shows basically that this is a problem for the whole city.”

Burdick-Will did not look specifically at the impacts of police violence on students, but she says it’s “part of the problem” given that “trauma is not necessarily directly related to having witnessed a crime, but it’s also related to living in a neighborhood where there is intense policing.”

Some may argue that you’re going to find low scores in classrooms where there are higher percentages of low-income students, and that poverty is more of an indicator of student achievement. However, Burdick-Will says that doesn’t totally apply to the peer spillover effects that she studied—”It not as obvious as to why you would do poorly in class because your classmates are economically poor,” she says. Poverty matters, says Burdick-Will, but proximity to students traumatized by violence has a stronger impact on peer academic performance.

“The effects of violence are not contained where it happens, and dealing with the immediate trauma of someone who has been involved in a particular event is really just the tip of the iceberg,” says Burdick-Will. “We are all socially connected to one another and therefore the effects of these things reverberate through the whole education system.”

Violence is certainly a problem in the small municipalities around Pittsburgh where Antwon Rose lived, went to school, and was killed. He was a student of the Woodland Hills School District, which is responsible for schooling the children of a dozen small municipalities including East Pittsburgh. Besides Rose, at least five other Woodland Hills students have been killed in the past school year alone.

Comments

Post a Comment